Rarely has the Confederation of African Football been more desperate for African football to do the talking on the pitch.

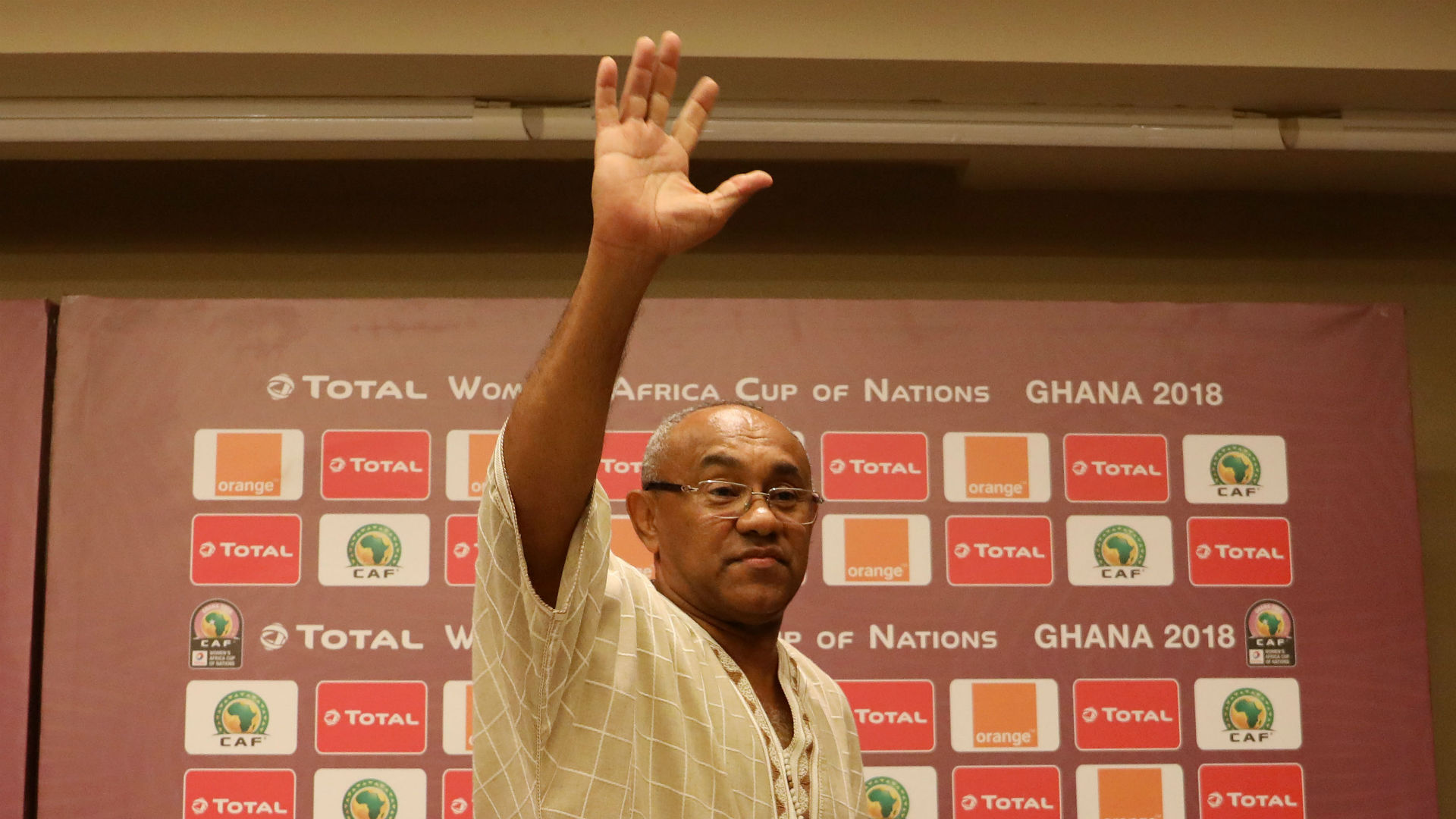

In recent months, the continent’s governing body has found itself increasingly embattled, with Caf officials being dismissed—seemingly on a whim—amidst bribery allegations, with accusations of the misuse of funds, and with an increasing scrutiny on the tenure of president Ahmad Ahmad.

The Malagasy football administrator ushered in a wave of positivity after being elected in the stead of his predecessor, the antiquated Issa Hayatou, in March 2017, yet to date, the jury’s out on his tenure.

Decisions to expand the Nations Cup to 24 teams and to shift it to June and July—from its traditional timing of January and February—was a bold move, but increasingly began to be seen as the new man attempting to lay down a marker, rather than a reasoned strategic approach.

The switch—which came despite the 2019 qualifying campaign already being underway—ultimately led to Cameroon—already appointed as hosts—being stripped of the tournament following a saga in which external auditors were brought into the country to assess their viability to accommodate 24 teams rather than the anticipated 16.

A backdrop of internal strife and political turmoil in the Central African country hardly helped—or perhaps made Caf’s ultimate decision a little easier—and a final, fatal decision for Cameroon was taken in November 2018.

Egypt saw off South Africa—emphatically—to host the tournament, only six months ahead of the kick-off, and you can imagine Ahmad breathing something of a sigh of relief when the competition was moved to Caf’s home city (the organisation’s headquarters is in Cairo).

However, in subsequent months, the president has been accused of cosying up to the Moroccan federation, and of being a puppet of Fifa President Gianni Infantino.

But still, no one expected the fiasco that enveloped the Caf Champions League final second leg between Wydad Casablanca and Esperance on May 31, when Ahmad was forced onto the field of play to implore the Moroccans to resume the match after it had been halted—in protest—after the referee refused to use VAR to reassess a goal that had been ruled out.

It ultimately emerged—and Caf really didn’t need anyone calling their competency into question—that the VAR equipment hadn’t been delivered in time, although there are differing reports as to whether the teams were made aware of this before the match.

As if Ahmad’s week couldn’t get any worse, he was detailed by the French police and questioned in relation to corruption charges, before later being released without charges. Fifa deemed fit, subsequently, to appoint Fatma Samoura as ‘Fifa General Delegate for Africa’ in a move to improve the continent’s football governance.

Ahead of the Nations Cup, from a media point of view, the inability of Caf to hand out accreditation in piecemeal, and not to respond to some requests until the days before the tournament—one journalist from a British broadsheet was refused entry to the opening match as his demand was still ‘pending’—has proved to be yet another stick to beat them with.

Amidst this backdrop, and underneath the watching eye of Egyptian president Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, Ahmad, Caf, and anyone concerned for the well-being of the continent’s favourite sport, will have been desperate for Friday night’s opener between Egypt and Zimbabwe—and the opening ceremony that proceeded it—to have transformed the narrative.

It certainly did that.

A 75,000-strong crowd at the Cairo International Stadium were treated to a pre-tournament ceremony which was a case of Cirque du Soleil meets The Mummy Returns.

It began with the Nile—depicted by a swathe of performers carrying metallic blue sheets—fluttering around the Giza Pyramid, a visual, vivid presentation of all of Africa congregating in Cairo as the river itself flows down from the continent’s heart—from Lake Victoria and beyond.

A technicolour Africa.#TotalAFCON2019 pic.twitter.com/AKOMnatuNW

— Ed Dove (@EddyDove) June 22, 2019

Spectators could feel the heat of a dozen electric flames set around the stadium as the spectacle proceeded, an attempt to upstage young Prince Moulay’s efforts at the African Nations Championship, perhaps—although this was a show primarily for the presidents, for the television, rather than the assembled Cairene masses.

Presumably, and mercifully, the Austrian acrobats who had been wheeled in for the draw in April stayed away, as the ceremony proceeded—a cross between a Nile cruise and the Crystal Maze, between Clean Bandit and Umm Kulthum.

There was energy and dynamism here, a stark contrast to Booba’s efforts to sing the 2017 Africa Cup of Nations to life in Libreville, and Caf somehow have a method of piping in audience sing-along sound to create the impression that half of Cairo was signing along with the latest Wes Madiko masterpiece.

It’s something that English football has never managed—I’m reminded of Chris Martin blaring out ‘Para, para, paradise’ solo, isolated, alone, in the Sheffield United end after their 2012 League One playoff final defeat by Huddersfield Town—and generates the effect that the whole stadium is partaking in and participating in the celebration.

This was the vision of a technicolour Africa; Ahmad’s vision, of glitz, glamour, French Euro beats, and of supervisors herding juvenile dancers—whose costumes must have been flammable—worryingly close to shooting cavalcades of fireworks, one of which needed to be put out by an extinguisher.

“A cross between a Nile cruise and the Crystal Maze, between Clean Bandit and Umm Kulthum.”#TotalAFCON2019 pic.twitter.com/AdBFoUsrve

— Ed Dove (@EddyDove) June 22, 2019

There must be chaos, after all, but you do wonder what Tutankhamun, upon whom the tournament’s mascot is modelled, would have made of it all.

Ultimately, the giant replica of the Giza Pyramid—not to scale—was folded down to reveal a giant replica of the Afcon trophy—not to scale—and six-metre statues of Egyptian gods—Horus, Anubis and the rest of the gang—were wheeled away to nearby gangways.

For half an hour, it had all been forgotten; the bribery allegations, Technical Steel, the dismissed ministers. Even Zimbabwe’s players, listening if not watching, must have been quietly relieved that threats to boycott the opener amidst unpaid allowances were not realised—this was an event you wanted to be at.

Finally, football was back; back in hearts, back in minds and, crucially for Caf, back in focus.

It’ll be the same again tomorrow, of course; there will be no plug sockets in the media centre, the wifi won’t work, more money will go missing…and Cameroon will go on strike, but this reminded Africa of what African football ought to look like, how it ought to feel, and why its odorous ills will be forgotten, for now…

Be the first to comment