Ben Thornley was in the Nou Camp on May 26, 1999. He should have been on the pitch. He should have been among those lifting the Champions League trophy, the final part of Manchester United’s remarkable Treble. But while his peers, friends and a group of players who at one time he was regarded as better than celebrated their own glory, Thornley was in the stands.

Of the “Class of ’92,” the extraordinary generation that formed the core of Manchester United’s great side of the 1990s and early 2000s, opinions varied as to who was the best. Ryan Giggs was the first to break through and became the first superstar. David Beckham went on to be the most internationally renowned. Gary Neville got every drop out of the talent he had. Paul Scholes, like a critically acclaimed artist, is usually the one who opponents say was the best. But when they were all in that youth team, the one that won the Youth Cup in 1992, it was Thornley who by common consensus had the most talent.

“Ben would have outdone all of us,” said Beckham. “England wouldn’t have had a left-wing problem for so many years,” said Nicky Butt. “He was one of — if not the — most talented members of that team,” said Neville.

Thornley should have been a key part of that United team, but in 1994, not long after he made his first-team debut, his knee was obliterated by a tackle in a reserve match. He was playing again six months later but was never the same. So rather than facing Bayern Munich on that night in Barcelona, Thornley was with the fans having signed for Huddersfield Town a year earlier.

Remarkably, Thornley’s primary emotion was joy rather than a sense of what could have been.

“The feelings, if I ever did have those, had long since evaporated,” Thornley tells ESPN. “That was in 1999; the injury happened to me in ’94. I quickly knew I was never going to be a first-team regular at United, even though I stayed there for another three-and-a-half years.

“I just got caught up in the game itself and the celebrations afterwards. It was a brilliant night, and it never crossed my mind once that this could’ve been me. I was just so thrilled for the boys I’d grown up with to be involved with such an incredible season.”

Five years earlier, the 18-year-old Thornley had been given the nod that he might be required for United’s FA Cup semifinal at Wembley but was instructed to tune up in a second XI game against Blackburn a few days before. Just over an hour in, he was asked if he wanted to come off with the big game in mind. He said no. Five minutes later Thornley played a 15-yard pass to Clayton Blackmore only for a 28-year-old defender named Nicky Marker to steam in and take him out with a late, dangerous challenge.

Everyone present didn’t so much see the challenge as hear it. There was a snap; an uncommon noise that, as it turns out, was the sound of everything in his right knee breaking. “While I was lying there [in the treatment room]” writes Thornley in “Tackled,” his new autobiography, “it suddenly dawned on me: this could be it.”

It wasn’t the end of Thornley’s career, but it was the end of what he could have been. In the book, Neville compares him to Eden Hazard in the way that he could shift direction and the ball so easily. But he couldn’t do that after the injury.

“I had two feet and was able to shift the ball by squaring up the full-back,” Thornley says, “either towards the touchline or coming back inside to whip a ball in with my right foot. That little half-yard was something that (a) they had to guess which way I was going, and (b) by the time they had, I had already gone.

“That was something that it quickly became apparent I didn’t have anymore. It was like having a piece of string or piece of wood: once you break it down the middle and try to repair it, it’s never as strong as it once was. When you’re talking about playing at the top level, you are talking about fine margins. That was the type of thing I relied on.”

In some respects it was a minor miracle that Thornley ever played again: he spent nearly four more years on the fringes of the United team, then in 1998 moved to Huddersfield. After three years there he went to Aberdeen, but beyond that he drifted. “I was a little bit aimless, I suppose,” he says. He drank heavily, enjoyed — according to the book, anyway — a lively personal life, and his professional career was basically over at the age of 28. That was a few months after United bought Cristiano Ronaldo.

“I can’t put everything down to that one tackle,” he says, when asked about the psychological impact of his injury, “but I’m sure there are people far more qualified than me who can trace what I’m like now as a person right the way back to it. It’s like you’ve had a fabulous party and you come home: there’s an emptiness there. That’s what I felt not going into a dressing room every day.”

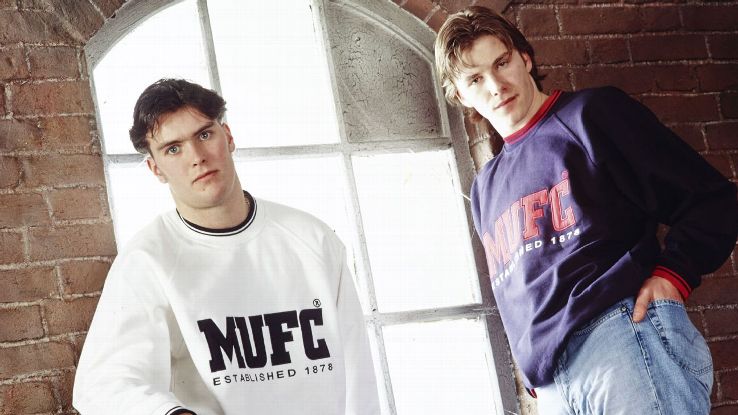

Ben Thornley grew up with David Beckham but was in the stands as his former teammate starred in the 1999 Champions League final.

Ben Thornley grew up with David Beckham but was in the stands as his former teammate starred in the 1999 Champions League final.

There are a couple of threads running through Thornley’s book that are potentially contradictory but suggest a man with a relatively clear head. Firstly, he doesn’t fudge the issue of blame: he places his inability to have the career he wanted firmly with the man he successfully sued (along with Blackburn Rovers) in 1999. “I don’t hold any sort of malice towards Nicky Marker but I do hold him responsible. Absolutely.” But at the same time, as his feelings about that Champions League final suggest, he says he is not “bitter or resentful” about how his career and life panned out.

“The negative emotions will just consume you. I needed to be in a frame of mind where I was thinking positive thoughts.”

That said, the injury clearly had a colossal impact. In the book, Thornley’s brother admits it changed him, that he’s “never been as happy as he was before” the injury. “I always tried to put a cheerful face on it,” Thornley writes. “I didn’t want anybody to feel sorry for me… But I’d love to have played 40 games for Manchester United without having had an injury at 18 years of age. Just to see.”

“I did know I was a good player,” Thornley says. “The only reason I can say that is Eric Harrison [Man United’s legendary youth team coach], after one of his famous bollockings we used to get from time to time, he’d say, ‘Don’t ever think you’re good players. You’re good players when I tell you.’ And he did tell me once. That was good enough for me.”

“Tackled: The Class of 92 Star Who Never Got To Graduate” by Ben Thornley and Dan Poole, is out on Oct. 15.

Be the first to comment